Vol. 38 (Nº 35) Año 2017. Pág. 41

Vol. 38 (Nº 35) Año 2017. Pág. 41

Harold Andrés CASTAÑEDA-PEÑA 1; Jorge Winston BARBOSA-CHACÓN 2; Marcela HORMIGA-SANCHEZ 3

Received: 27/03/2017 • Approved: 30/04/2017

6. Conclusions and projections

ABSTRACT: This qualitative-exploratory research study inquiries about the potential relationships between information literacy competence (ILC) and foreign language competence (FLC) in the context of English for Specific Purposes (ESP) course. Sophomores studying Business Management participated. Findings show that sophomores demonstrate poor language learning background and tend to cut, paste and translate information. It was found that most sophomores do not find support in their language teachers to comply with academic tasks. Curricular implications of putting together ILC and FLC are discussed. |

RESUMEN: Este estudio cualitativo y exploratorio indaga las relaciones potenciales entre competencias en lengua extranjera e informacionales en el contexto de un curso de inglés con propósitos específicos. Participaron estudiantes universitarios de Administración de Negocios. Los resultados indican que ellos tienen un pobre antecedente de aprendizaje del inglés y que tienden a cortar, pegar y traducir. La mayoría de estos estudiantes no han tenido apoyo de sus profesores de inglés para el desarrollo de tareas académicas. Se discuten implicaciones curriculares. |

The concern about the complementarity between information literacy competences and academic competences has been recently explored in educational contexts at university level (Hegarty and Carbery, 2010; Pritchard, 2010; Price, Becker, Clark and Collins, 2011; Wang, 2011). However, research studies exploring the interphase between foreign language competence (FLC) and information literacy competence (ILC) in English for specific purposes (ESP) courses appear to be less apparent in the specialized literature (but see Hormiga-Sánchez, Barbosa-Chacón, Castañeda-Peña and Marciales, 2014).

There are attempts to explain this interphase in the context of English as a Second Language (ESL). ESL from that standpoint broadly means that language and information users are geographically situated where the second language is spoken as an official language for daily communication. For example, Prucha, Stout and Jurkowitz (2007) created a curriculum for ILC keeping in mind principles of second language learning and concluded form the experience that “the resulting information literacy curriculum in ESL has established a versatile collaborative framework that can be used by librarians in working with their own ESL departments or with other disciplines” (p. 25). Prucha’s et al’s (2007) findings are relevant yet it is necessary to explore contexts where English is considered a foreign language. English as a Foreign Language (EFL) is understood as an additional language used for specific purposes in contexts where English is not formally used in a day-to-day communication basis. Just a few experiences in this context have been already documented (Valdez and Solis, 2005; Solis and Valdez, 2006 and Valdez, 2012) in Latin America. Given the great amount of academic information published in English, it seems paramount to explore how ILC relates to users whose first language is not English and who are educated in EFL contexts. This then appears to be a spring board to comprehend how ILC is enacted when users relate to information in a language which is not their mother tongue.

This study4 then initially explores the potential complementarity (if there is any) between ILC and FLC. The study enquires such complementarity in the context of an ESP course taken by university students.

This section goes into two parts. Firstly, a revisited concept of ILC will be introduced briefly addressing part of its history and modal components. Secondly, based on the concept of academic literacy (Street, 2009) an understanding of academic-information literacy in ESP will be sketched.

Most theoretical and research contributions on ILC appear to have been based on the concept proposed by the American College and Research Library (ACRL, 2000) and the American Library Association (ALA, 1989). Drawing on such perspective, being informationally competent implies having the ability to locate, organize, evaluate and use information. Two main features have been highlighted by the specialized literature about this understanding of ILC. Firstly, the concept emphasizes on the acquisition, development and demonstration of individual skills. Secondly, the concept relates to the identification of practices regarding search, evaluation and use of information. The ILC concept has been re-visited (Marciales et al, 2008) taking distance from the aforementioned features.

This revisited concept of ILC acknowledges three historical strands in the evolution of ILC in Science Information: i) the predominance of an objectivist perspective in which evaluation was centered around the measurement of knowledge provided by tests; ii) the importance given to the processing of information and iii) the embedding of the concept in the cultural and social environments, such shift happened thanks to the influence of Vygotsky (Montiel-Overall, 2007). The most important aspects of this last strand are explained in chart 1 and are understood as the foundations for a revisited ILC concept.

Chart 1. Sociocultural perspective in ILC

|

INFORMATION LITERACY COMPETENCE VIEWED FROM A SOCIOCULTURAL PERSPECTIVE |

Variables |

-Culture is inseparable from the way human beings feel and learn. -Human activity is located in the context of social and cultural interaction. -Interaction with others is seen as a mediator in the creation of knowledge. -Cultural and contextual differences are seen as the base to configure common place ideas and practices. |

Principles |

-Sociocultural factors exert influence in the evolution of competencies. -Culture mediates the way the subject builds meaning from information and the way he interacts. -Competence is flexible and dynamic. |

Features |

-The authority embedded in individuals and communities to create, evaluate and use information is acknowledged and not just the authority in sources validated by scientific communities. -It is understood that information might be biased, therefore, to become informationally competent means to develop the capacity to identify such trades. -Information does not exist as an objective reality, it is built by individuals within a sociocultural context and it is continuously transformed by reality. Information is an instrument to create knowledge influenced by cultural factors that are associated by the way information is created in communities, the way it is transmitted and the context in which it is used. |

Information competence is seen as a practice of the social and cultural dimensions. It presupposes the existence of a link between its development and the formation of a social being, capable of assuming, critically and ethically, the diversity of cultural factors mediating the access to information. |

|

Historical dimension of the informational competence: -The information user is “a dynamic and changing subject”. -The subject’s history is built based on what is remembered and forgotten. Such personal history establishes continuous and discontinuous threads regarding the way to access, evaluate, use and internalize information. -New instruments and practices coming from the interaction of communities of information users are relevant for these subjects because they influence beliefs and practices. -Interactions are configured as an instrument to build meaning and they are expressed in the common ways of associating to information in specific contexts. -The internalization of information, in specific cultural contexts, represents a fundamental role for the development of competences and social capital. |

Source: Adapted from Marciales et al (2008) and Barbosa-Chacón et al (2010)

As argued above, these variables, principles and features shape a revisited IC concept (Marciales et al, 2008) that shifts from the traditional definition in the following way:

IC is a deep tapestry of intertwined epistemic subject’s adhesions and beliefs, motivations and attitudes built along his/her personal history in specific formal and informal learning contexts. Such tapestry is used as a frame of reference relating myriad ways to internalize information which are consequently represented in the access, evaluation and use of data; such internalization processes are perceptible in the cultural contexts in which they were formed (Marciales et al, 2008: 651).

Thus ILC is thought of as a theoretical construct substantiated by four modal structures: Potentiality, virtuality, performance and realization (Greimas, 1989; Fontanille, 2001; Alvarado, 2009; Gualdrón de Aceros, Barbosa-Chacón y Vásquez, 2010). For Greimas, competence is configured as the becoming that precedes its own realization. Consequently, competence is constituted by the previous modalities that make action possible (Alvarado, 2009). From the aforementioned contributions, the subject that uses information sources is made up by his/her performance which is influenced by different modalities: knowing, being-able-to, wanting and having-to. Finally, when the subject is modalized by his/her beliefs this indicates the subject has assumed the parameters of his/her culture and social group (Alvarado, 2009). The levels or modes of existence of ILC are explained in Chart 2. They are the integrating and articulating elements of ILC and also provide a frame to profile information users (See Castañeda-Peña et al, 2010).

Chart 2. ILC modalities

ILC MODALITIES |

|||

POTENTIALITY |

VIRTUALITY |

PERFORMANCE |

REALIZATION |

Beliefs |

Motivations |

Attitudes |

Actions |

Determined cultural adherences |

Wanting |

Knowing |

Becoming |

Having-to |

Being-able-to |

||

This modality encompasses value systems which are perceptible when standpoints are put forward regarding a problematic situation, a necessity, a topic or a challenge |

This modality is related to one’s own will or duties which are the motivations to foster actions

|

This modality refers to the knowledge one possesses about what to do and how to perform an action |

This modality regards the perceptible execution of the IC realized when using information sources. This relates to how information is appropriated and communicated |

Source: Adapted from Barbosa-Chacón et al. (2014).

This vision of ILC relates directly to the new literacy studies movement when studying ILC in an academic context where the language of instruction is a second one (e.g. English (see research participants below)). In this line of thought, Street (2009) has understood academic literacy as a contextualized practice in a specific academic domain. Thus, the use of ESP in an academic domain may well be understood as any schooled literacy practice where it is necessary to make ILC happen. That is why it is likely to talk about academic-information-literacy competence in ESP. In that sense, it could be argued that language competence complements students’ ILC and vice versa. This is possible because it is assumed that in ESP courses the focus lies more on the language in use standpoint (e.g. reading and writing (Hermida, 2009 and Grabe and Stoller, 2001)) than in teaching pure grammar and linguistic features. Being language competence integrated into the professional development of university students, ILC becomes paramount as part of this subject matter (e.g. ESP). As stated before, this complementarity of competencies appears to be under researched.

This is a qualitative study that explores the complementarity of language competence and ILC in the context of a genre-based task occurring in an ESP course at university level.

3.1 The Business Management Program

The Business Management Program is a hybrid program at the Institute for Regional Projection and Distance Education at a public university in Santander (Colombia). The undergraduate program combines virtual courses in Moodle with the support of tutors in face-to-face sessions. The programme lasts five years, and, due to the advantage of combining virtual resources with on-site support it is taught in different municipalities in the state of Santander by making use of Student Attention Centers (SAC) that belong to the University.

3.2 Research participants

The research participants (RPs) for this study were 37 Business Management sophomores who were about to begin their first course of ESP (English I) during the second academic semester of 2012. The RPs were based in the municipalities of Barbosa and Bucaramanga (Santander). The average age was 29 years old and the student population ranged from 19 to 46 years old. Such range is common for people who combine study and work thanks to the offer of distance and virtual study programs (Toro and Rama, 2013). Among the RPs 73% were female and 27% were male. This gender distribution at the study program is a tendency of the total student population at the university (UIS, 2013). All participants have Spanish as their first language and are required to take a component of ESP in their program of study. Students receive an introductory course to library use but information literacy courses are not taught directly.

3.3 Procedures

The procedure for data collection was structured in two main components. The rationale for such procedure can be seen in Castañeda-Peña et al (2010), Barbosa- Chacón et al (2012) and González et al (2013). The first component to collect data consisted of the following three elements:

3.3.1. Foreign language and information literacy profiling questionnaire

From the perspective of the self as stated by Navarro (1995), this questionnaire helps to identify the practices that students perceive as usual in how to access, evaluate and use information when facing a task in the foreign language.

3.3.2. Task

Research participants were assigned a task designed meeting Hofer’s (2000) criteria. Firstly, this should be subject of scientific research. For this study, research participants had to find out information related to entrepreneurial content (genre-based task) to create a business proposal to be presented at a business school abroad in order to get financial support. Secondly, the task should generate interest in university students. All research participants belonged to the Business Management programme offered at the Institute for Distance Education at the University; therefore, entrepreneurship was chosen to be the task’s theme since it is a fundamental topic throughout the core subjects. Finally, the task should involve information search processes. Research participants were given a computer with internet connection and access to data bases. The task initiation was performed in twenty minutes and participants were also instructed to use a thinking aloud protocol (Ericsson & Simon, 1993) strategy to record data about the procedure followed. During this initial stage, the students were asked to inform orally what they were thinking while doing information search.

3.3.3. Semi-structured interview

This was used to unveil the rationale research participants manifested to have underpinned their actions while on-task. This interview explored aspects of the research participants’ academic and personal experiences intertwining EFL and ILC competences. Interviews were recorded and transcribed. They were also conducted in Spanish and translated into English.

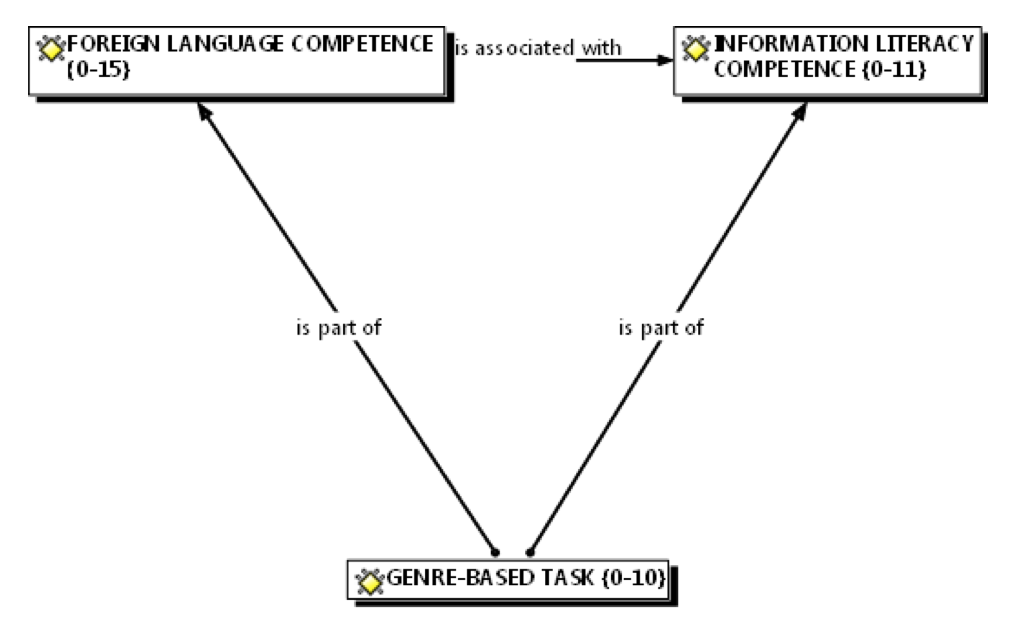

The second component involves the recording and analysis of data. For this, a closed system of three previously defined categories was used along with elements of grounded theory (Strauus & Corbin, 2002). This helped determining emergent codes of behaviors, events and processes occurring while the task was carried out. The data was analyzed using AtlasTi, a software specialized in assisting the treatment of qualitative information including speech, video, images and recordings. As a result, a model of analysis was obtained as illustrated by Figure 1. The pre-established categories correspond to foreign language and information literacy competences and to genre-based tasks.

Figure 1. Framework to study foreign language learning and information literacy in higher education

Each of the three pre-established categories will be presented now with a description of the emergent codes that characterize them. This presentation will be backed up with data taken from the interviews, the out loud protocols and the profiling questionnaire.

In relation to information literacy it was found that FLC competence is substantiated by adherences to the foreign language and to its learning while undertaking the ESP course. This implies to keep in mind participants’ background and awareness about their own competences and how they plan on strategies to search for information in the foreign language. This is shown in figure 2.

Figure 2. Foreign language competence in the context of a genre-based task

Actual target language experiences appear to have a great impact on the task achievement designed for this study. RPs are not used to write long texts or to send out applications abroad. However, RPs recognize the importance of English for the work place and for a better professional future. In RP7’s words: “we have been demanded a lot for example in our English 1 course… when we took that course we had to translate a lot, talk to a classmate… Ehmm.. and what I mean… that’s good because one practices the language…” (P7:50).

This indicates that RPs tend to perceive that language learning requires a lot of effort and this depends to some extent on the language course requirements and the type of activities students face. In terms of self-study, RP5 affirms that “understanding vocabulary has been difficult, we have to play back the self-study audio many times to understand… (P5:52).

This resonates with the development of self-study foreign language learning strategies. RP1 comments that “one understands because one watches TV and listens to music… so one gets better… at least I compare a lot of sounds… so I’m one who… I’m the one who compares sounds… kinda…” (P1:54) and in RP4’s case “I focus on things and spend time, I analyze and ponder… yes this works… this doesn’t work… this does… this coheres… I try to interrelate everything…” (P4:73).

In spite of the fact that students perceive different levels of difficulty and tackle them developing self-study strategies, motivation towards the foreign language is at times affected. Some students perceive that they do need to start off language classes implying that the university’s language courses are not enough. For example, RP1 has planned “on studying language elsewhere because I cannot… I have to drop and start off next year to study… English” (P1:52). RP3 argues that “I have always wanted to study English… but the moment is not there yet” (P3:21).

In this sense, students also recognize how much they have invested in their own language learning “I never failed English but I was not that into it… nothing dealing with English” (P4:44). On the other side, there are students who claim that “I might not be that good at it but I’m interested” (P5:34). This mixture of feelings towards achievement in language learning is correlated to the sources used to study in the target language. Most RPs declare using dictionaries and on-line translation devices. They include Phonetizer® (P2:25), Babylon® (P4:36), Wordreference® (P5:83; P7:19) and their pocket Laurosse® and Chicago® dictionaries (P5:28; P7:47).

What seems to be relevant for the purposes of this research study is that the RPs consider those resources very reliable to cope with their academic work in the foreign language. This happens in an instrumental way “well --- here it (information) pops up in English… Information … so… what is what I do?… cut it… and then paste it into the translator” (P4:61) or this simply has been advised by teachers as stated by RP5: “our teacher [name] gave us a reference list and she suggested that dictionary and I looked up words on it and wrote the texts” (P5:65). All this appears to be in direct relation with RPs previous experiences with EFL.

According to RP1 “my English language background is too bad” (P1:56) referring to the previous high school experience as foreign language background. This could be attributed to the fact that in the late 90’s there was not learning support, just “a little book a regular paper dictionary.. one that it’s found anywhere.. maybe a dictionary widely used… I don’t know… there was not Internet… didn’t use it back then…” (P2:39). There appears to be a combination of age and curriculum for these adult learners as expressed by RP3 when claiming that “people from my generation have none or little high school education in English because I studied English but not that much... just the basic things like verb to be… that you should learn the verbs by heart” (P3:24).

One way RPs use to coming to grips with their language learning is resorting to family members/friends contact with the foreign language just because they establish comparison criteria or because they felt amazed about how much new generations are achieving in language learning terms. For example, RP1 states, talking about his son, that “can you imagine? He is 5 years old and already knows English… he studies more hours at school than I do compared to all my school experience…” (P1:50). This appears also to be the case for RP6 “for example, I’ve got a two years old boy, two years and two months. And he knows more English than I do (laughter)” (P6:51) and for RP7 “think of this… my seven year old daughter already knows the colors the numbers… the… I mean many things in English” (P7:43). RP3 assesses his friends’ experiences “I’ve got Friends who have spent lots of money in English courses… they survive a bit… they might lack pronunciation skills… and obviously their vocabulary is not that rich… and other things”. All in all, this reinforces the idea of not being proficient enough to cope with tasks in the foreign language and the ESP course.

This resembles RPs’ awareness of foreign language performance. At the same time this demonstrates how language learning is understood by the RPs. They appear to hold a structural view that is transferred into their own learning practices. This could be substantiated in terms of contrastive analysis theories where the first and the second language are compared constantly (Laufer & Girsai, 2008). For example, “one’s own mistake is that when writing in English one thinks in Spanish” (P1:37). This could also be anlyzed in major studies in terms of error analysis as RP5 implies when states that “at time one makes mistakes in Spanish… in English this could be worse if one does not know enough” (P5:99). The level of proficiency is then contrasted to real life situations “I have suffered a lot because of English or… not suffer a lot… I have rather missed a lot of professional opportunities… so obviously… I know nothing about English” (P7:34-35).

In the same line of thought, RPs appear to be aware of peers’ information literacy skills in the foreign language. For instance, the age factor is perceived as a common feature affecting school achievement: “no one has had really the time… to study English seriously…” (P1:47) because “the younger students are better than us the old ones… they have their language knowledge fresher and they access to information in English easily and we are really stuck” (P5:87). However, there are certain linguistic skills (e.g. Reading) in which adult learners could outstand: “there are other friends who just read well in English and that is enough for them…” (P3:76). All this makes RPs aware of what pathways to take when facing information literacy tasks in the foreign language.

Information competence profiles are not fixed but fluid and they come together in different ways depending on the academic task at hand (Castañeda-Peña et al, 2010). These profiles appear to be transferred to conduct information research in foreign language. For academic tasks in first language, it has been identified that university students could be information collectors, information checkers/verifiers and reflexive (Castañeda-Peña et al, 2010). One of the main features with information collectors is that they tend not to plan their information search (Castañeda-Peña et al, 2010; Barbosa-Chacón et al, 2010; Hormiga et al, 2014). This lack of planning ends up in using as a search starting point Google®. This also concurs with the RPs’ experiences in this study. When asked about how they started off their search for the task, they all tend to agree on using the same search engine at hand: Google® (P1:67, P3:41, P4:49, P5:3, P6:3, P7:56).

Their search strategy appears also to be unplanned but specific micro-skills related to search information appear to be developed. For example, RP1 does not have a foreign language high proficiency level, so the search in Google is conducted via word-by-word translation from Spanish into English in order to have a vocabulary list useful for developing an academic task. RP3 tends to do the same with an apparent control on information selected by the search engine “well... what I do know how to do is as my teacher advised, ctrl copy and ctrl paste, but as I said before just by bits, by fragments…” (P3:79-80). There is also a tendency to evaluate the type of information that best suits the task, for example RP4 claims “I start scanning and… I look for what I can find useful…what information is there and what Works or does not work…” (P4:67), then RP4 translates trying to make sense in the foreign language “and if there are things that do not cohere at all… I try to make them fit” (P4:119). This student verifies the resulting translation by translating back into Spanish and by contrasting back and forth translations in both languages; this skill was developed on her own at the university. This is a strategy that RP5 also utilizes: “then the translator shows the thing in English… and what I do… eh… is to translate back into Spanish word by word, for example, in this case I would need to type in… emprendedor (entrepreneur)… that is what I do to know if the word is spelt correctly… so I double check” (P5:36). RP6 collects information, then translates and verifies if the translated information is ok by looking up words in a dictionary or by translating back and forth as well. This strategy is also shared by RP7. All in all, these findings demonstrate that information collectors transfer the “cut and paste” skill into foreign language information use and additionally, they translate word by word or larger pieces of texts (paragraphs) and double check meaning in the target language by using dictionaries, e-translators or by translating back and forth in both languages. This appears to be determined as well by the type of academic task.

Both the search starting point and the search strategy appear to condition what is done in the academic task in terms of new adherences, the task on its own and actual performances in the foreign language as it is shown in figure 3.

Figure 3. Information literacy competence in the context of a genre-based task

It appears that searching for information in English is frustrating for the RPs. They however are aware of the fact that there is a lot of related information on Internet; their major difficulty consists on assessing quality so that they end up adhering to specific information sources or liking printed sources: “so untrustable info here because you might find lots of information in there but no… this is not info one could trust. So what I really like is to search in books” (P1:213). In the same line of thought, RP2 claims that “in general I like reading… I am no such a good reader but I like reading… I mean, I trust books I still trust them… right? I like them… I like… I still carry out my books rather than looking for information in Internet” (P2:246). They also tend to search on pages very-well known to them “for example that one called "Fonetizer" because one uses it during the whole course, right? And since it is used for everything… and as it has been recommended one uses it all the time…” (P2:163) or in web pages that have been recommended; for example, “that page is what comes in handy… another translator? Well it is easy to use and it is the only one I know… as I said… do not know another one… I think there are more and perhaps more friendly user but this is the one I know and I just translate by parts…” (P3:60). RP5 uses the e-translator because according to his own experience this speeds up the process. RP5 and RP6 trust Wikipedia. What could be gained from this is that there are adherences to specific sources of information but students appear not to have elements to assess if the information sources they deal with are trustable or not. It is simply their intuition what says if what is found in Google is whether or not reliable. What seems important is that students feel responsibility for their academic task.

All RPs focused on the topic of the task finding out about their entrepreneurial idea. RP1 wanted to promote an idea of fashion design (e.g. bridal dresses); RP2 and RP6 were looking into recycling as part of social responsibility (e.g. biodegradable industry); RP3 and RP5 thought of entertainment setting up bars (e.g. theme-based bars); RP4 wanted to dive into the shoes industry and RP7 wanted to produce hand-made candies. There was for each independent focus a degree of information literacy task awareness. This is to say that RPs knew about the macrostructure of the document to be handed in and that they were aware of searching for information to produce an interesting proposal that complied with the task requirements. In the in-depth interviews; RPs were able to describe this but pointed out the difficulty of developing the academic task in the target language directly, “and I’ve got all the info needed… but is it in English?” (P1:56). It seems common for them to create their texts in Spanish first and then to translate them into English: “Writing up an essay… explaining one’s own entrepreneurial idea… keeping in mind the essay parts… I mean title, introduction, body and conclusion… a five-paragraph essay… hmmmm… but written in English… I did it in Spanish and just what I have to do is to translate it” (P3:37-46). This shows that RPs understand to what extent their education in the target language has been successful

It is evident from the data that RPs are aware of peers’ information literacy skills in the foreign language as explained above. If the conditions of the task were changed (e.g. students are given two months to develop the task), some RPs would change their strategy to embrace this as demonstrated with the hypotheses they made about information literacy performance in the foreign language. Some of them acknowledge that if they were provided with more time for the task they would try to start off writing in the target language without translating “looking for someone to proofread the text” (P1:239). Others, being aware of their own target language proficiency say that “I will do exactly the same, I would translate” (P3:190); “basically… what can I say?… to be honest... so I mean I don’t speak English” (P5:131). This language education received by the RPs so far appears not to help them with academic tasks in the target language. This is not different from how they feel when it comes to find information for academic tasks with a crosscurricular vision. They study finance and economy and in none of these professional core subjects RPs tend to find a way out from the language perspective nor from the information literacy perspective. So, one could wonder about not only the curriculum but the role of mediators in a distance learning programme where there is an upfront target language component and a more invisible information literacy one.

Figure 4 illustrates that the academic task (e.g. filling in an application form with a supporting essay to obtain financial aid from an abroad company) which is specific to a disciplinary profile (e.g. business administration students in a distance learning programme) is highly associated to the role of the mediator by the RPs.

Figure 4. Genre-based task relating foreign language and information literacy competencies

RP1 considered that in order to cope with tasks like the one used in the present study it is acceptable to ask someone else to translate it. What is not stated is whether the translator would be acknowledged. According to RP1 this is more a type of collaboration as the central idea comes originally from her own authorship. This resonates with RP3’s idea of having back up with “someone who knows how to read in English and that makes a fine interpretation of what one writes telling how accurate the text is” (P3:90). Both RP1 and RP3 express the need for validation of their academic task in the form of a translation or in the form of a proofread text by an expert in the language. This is also shared by RP6. RP2 feels at ease going to the university language institute and asking an instructor or tutor to solve his linguistic doubts, this is something he is used to do. He however finds most language teachers busy to help him as at times e-mails are not replied back. In RP4’s case there has been help from his family: “Dad always paid for a home-tutor for me” (P4:160). Unfortunately, and as it seems recurrent in the data, RP4 feels no support from the English language teachers he has had in the distance-learning programme.

After analyzing the three pre-established categories it could be argued that the RPs’ academic-literacy practices in English involving information literacy skills tend to be guided by three main features. Firstly, in terms of the foreign language competence, RPs do not demonstrate a high level of achievement in the language-in-use dimension especially when tackling a genre-based task. This tends to be substantiated by a poor language learning background and by the transference of a skill in which information is cut, pasted and translated. This is so in spite of the fact that there is a will to learn the language and there is awareness of poor development of information literacy skills. Secondly, in relation to the information literacy competence, RPs tend to develop information collector skills as also demonstrated in the first category. No traces of other information literacy profiles (see Castañeda-Peña et al, 2010) were found in the data. Additionally, just one search engine is used (e.g. Google®) and the information found is simply translated appealing to known or recommended web applications that make this task easier. The core subjects RPs are undertaken in their undergraduate studies appear not to be helpful in the development of either of the competences: linguistic and informational. Thirdly, it was found that most of the RPs do not find support in their language teachers to comply with the task. These findings have implications in terms of a more desirable relationship between language learning and information literacy development in ESP courses.

Genre based-tasks could comprise an effective way to stimulate and motivate bidirectional learning (toward information literacy competence and foreign language competence) because if would help students to use a foreign language and develop strategies to seek and use information in this language to create new discussions on topics relevant to their current study program. Potentially, ESP courses at higher education could become the bridge for such bidirectional learning in geographical contexts where English is not spoken as the main means of communication. At the curricular level this seems fruitful for the future professional development of university students and their actual academic performance not only at the linguistic level but also at the information literacy level. It seems that both EFL and ILC competences could be developed simultaneously but more research is needed to substantiate this claim. It seems necessary to keep exploring ILC as a constituent feature of academic-information literacies in ESP and in second and foreign languages in general. Arguably, all the competence modalities mentioned in the theoretical framework interweave together in a situated context where information tasks (or genre-based tasks) are to be carried out in a language different form one’s own be it for general, academic or specific purposes. In this study, ESP is seen as an academic literacy closely related to students’ professional development or to students’ vocational jobs (Harding, 2007, Long, 2005). In order to develop such sense of ‘purpose’, language students have not only to develop aspects of language learning but competencies that allow them to relate to information in order to enhance their vocational purposes and life-long goals. This could give a new direction to research about ESP within a frame that explores EFL and ILC development.

Alvarado, G. (2009). Competencia, Acción y Pensamiento: Una mirada a las posibilidades de uso del concepto de competencia en la pedagogía. Revista Científica “Gereral José Maria Córdoba”, 7, 56-64.

American Library Association (1989). Presidential Committee on Information Literacy: Final Report. Association of College and Research Libraries. Recuperado de http://www.ala.org/ala/acrl/acrlpubs/whirtepaper/prsidential.ttml

Association or College and Research Libraries (2000). Literacy Competency Standards for Higher Education. Recuperado de http://www.ala.org/ala/acrl/acrlstandards/informationliteracycompetency.html

Barbosa-Chacón, J., Barbosa, J., Marciales, G., y Castañeda-Peña, H. (2010). Reconceptualización sobre las competencias informacionales. Una experiencia en la Educación Superior. Revista de Estudios Sociales, 37, 121-142.

Barbosa-Chacón, J., Marciales, G., y Castañeda-Peña, H. (2014). Caracterización de la Competencia Informacional y su aporte al Aprendizaje de Usuarios de Información: Una experiencia en la formación profesional en psicología. Investigación Bibliotecológica (En edición).

Castañeda-Peña, H., González, L., Marciales, G., Barbosa-Chacón, J., y Barbosa, J. (2010). Recolectores, Verificadores y Reflexivos: perfiles de la competencia informacional en estudiantes universitarios de primer semestre. Revista Interamericana de Bibliotecología, 33(1), 187-209.

Ericsson, A., Simon, H. (1993). Protocol analysis: Verbal reports as data. Revised ed. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Gonzalez, L., Marciales, G., Castañeda-Peña, H., Barbosa-Chacón, J.; Barbosa, J. (2013). Competencia Informacional: Desarrollo de un instrumento para su observación. Lenguaje, 41(1), 105-131.

Grabe, W., & Stoller, F. (2001). Reading for Academic Purposes. Guidelines for the ESL/EFL Teacher. In Celce-Murcia, M., Teaching English as a Second or Foreign Language (pp. 187-203). Boston: Heinle & Heinle.

Gualdrón de Aceros, L., Barbosa-Chacón, J., Vásquez, C. (2010). La perspectiva semiótica como base para la construcción curricular. Una apuesta de la UIS hacia la Formación Regional en Agroindustria. Revista de Pedagogía, XXX (89), 277-306.

Greimas, A. (1989). Del sentido II: ensayos semióticos. Madrid: Gredos.

Harding, K. (2007). English for Specific Purposes. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hegarty, N., & Carbery, A. (2010). Piloting a dedicated information literacy programme for nursing students at Waterford Institute of technology libraries. Library Review, 59(8), 606-614.

Hermida, J. (2009). The Importance of Teaching Academic Reading Skills In First-Year University Courses. Recuperado de http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1419247 on 2014/07/05

Hofer, B. (2000). Dimensionality and disciplinary differences in personal epistemology. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25, 378-405.

Hormiga-Sánchez, M., Barbosa-Chacón, J., Castañeda-Peña, H. y Marciales, G. (2014). Competencia informacional en lengua extranjera en estudiantes universitarios de Colombia. Ciencia, Docencia y Tecnología, XXV (48): 13-47.

Laufer, B., & Girsai, N. (2008). Form-focused Instruction in Second Language Vocabulary Learning: A Case for Contrastive Analysis and Translation. Applied Linguistics, 29 (4): 694-716. doi: 10.1093/applin/amn018

Long, M. H. (2005). Methodological issues in learner needs analysis. In M. H. Long (Ed.), Second language needs analysis (pp. 19-78). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Marciales, G., González, L, Castañeda-Peña, H., & Barbosa-Chacón, J. (2008). Competencias informacionales en estudiantes universitarios: una reconceptualización. UniversitasPsychologica, 7 (3), 613-954.

Montiel-Overall, P. (2007). Information Literacy: Toward a Cultural Model. Canadian Journal of Information and Library Science, 31 (1), 43-68.

Navarro, P. (1995). La encuesta como texto: un enfoque cualitativo. V Congreso Español de Sociología, Granada, septiembre de 1995. Recuperado de http://home.dsoc.uevora.pt/~eje/pesquisa_enquanto_texto.html

Price, R., Becker, K., Clark, L. & Collins, S. (2011). Embedding information literacy in a first-year business undergraduate course. Studies in Higher Education, 36(6), 705-718.

Pritchard, P.A. (2010). The embedded science librarian: partner in curriculum design and delivery. Journal of Library Administration, 50(4), 373-396.

Prucha, C., Stout, M.A., & Jurkowitz, L. (2007). Information literacy program development for ESL classes in a community college. Community and Junior College Libraries, 13(4), 17-39.

Fontanille, J. (2001). Semiótica del Discurso. Lima: Editorial Universidad de Lima.

Solis, B. and Valdez, J. (2006). Los recursos de información electrónica de la Biblioteca “Stephen A. Bastien”: Un apoyo al curso de formación de los profesores del centro de enseñanza de lenguas extranjeras de la Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Virtual Educa. Bilbao (España), 20-23 junio. Recuperado de http://reposital.cuaed.unam.mx:8080/jspui/handle/123456789/1036

Strauss, A., and Corbin, J. (2002), Bases de la investigación cualitativa. Técnicas y procedimientos para desarrollar teoría fundamentada. Medellín: Editorial Universidad de Antioquia.

Street, B. (2009). The future of social literacies. In Baynham, M. and Prinsloo, M. (Eds). The Future of Literacy Studies (pp. xx-xx): Palgrave MacMillan.

Valdez, J., y Solis, B. (2005). La formación de usuarios un elemento de apoyo para el Curso de Formación de Profesores del Centro de Enseñanza de Lenguas Extranjeras (CELE) de la Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM). Encuentro internacional de Educación Superior – UNAM.

Valdez, J. (2012). La formación de usuarios en el Centro de Enseñanza de Lenguas Extranjeras de la UNAM: una experiencia de trabajo de más de diez años. En Hernández, P (Coordinadora). Tendencias de la Alfabetización Informativa en Iberoamérica. Centro Universitario de Investigaciones Bibliotecológicas. México: UNAM. (pp. 209-232).

Wang, L. (2011). An information literacy integration model and its application in higher education. Reference Service Review, 39(4), 703-720.

1. Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas. Profesor del Doctorado Interinstitucional en Educación, Énfasis en ELT EDUCATION. Doctor en Educación de Goldsmiths, University of London. Integrante del grupo de investigación Aprendizaje y Sociedad de la Información de Colombia. Email: hacastanedap@udistrital.edu.co

2. Universidad Industrial de Santander (UIS). Profesor titular del IPRED-UIS. Magister en Informática-UIS. Integrante del grupo de investigación Aprendizaje y Sociedad de la Información. Email: jowins@uis.edu.co

3. Universidad Industrial de Santander (UIS). Tutora del IPRED-UIS. Licenciada en Inglés. Integrante del grupo de investigación Aprendizaje y Sociedad de la Información. Email: fmh788@gmail.com

This study draws on a major study named “English with a Purpose” sponsored by the Colombian Administrative Department of Science, Technology and Innovation, the Research Division at UIS and the research group Aprendizaje y Sociedad de la Información.