Vol. 38 (Nº 34) Año 2017. Pág. 12

CASTILLO-PALACIO, Marysol 1; BATISTA-CANINO, Rosa M. 2; . ZUÑIGA-COLLAZOS, Alexander 3

Recibido: 16/02/2017 • Aprobado: 22/03/2017

ABSTRACT: This article is theoretical and conceptual, and aims to identify previous studies that have estimated the relationship between the cultural dimensions of the GLOBE project and entrepreneurship. Among the most important current theories that attempt to explain the relationship between culture and entrepreneurial activity is the Institutional Economic Theory of North. On the other hand, GLOBE raises nine cultural dimensions to identify cultural practices and cultural values of a society. From these cultural factors authors have developed studies that conclude that the dimensions that are related to business activity. Key words: Culture, Entrepreneurship, GLOBE Project, New Institutional Economics (NIE) |

RESUMO: Este artigo é teórico e conceitual, cujo objetivo é identificar estudos anteriores têm abordado a relação entre as dimensões culturais propostas pelo Projeto GLOBE e empreendedorismo. Entre as correntes teóricas mais importantes que tentam explicar a relação entre cultura e empreendedorismo é a Teoria Econômica Institucional do Norte. Além disso, o projeto GLOBE envolve nove dimensões culturais para identificar práticas e valores culturais de uma sociedade. A partir desta perspectiva, outros autores realizaram estudos em que se concluiu que essas dimensões culturais estão relacionados aos negócios. |

The essence of entrepreneurship is the initiation of change through creation or innovation (Morrison et al., 1999). New markets, customers and jobs are created through innovation and organizational renewal, which create an impact on both the social and economic systems of industrial sectors, regions and nations (Morrison et al., 1999). Entrepreneurship is considered a systemic phenomenon, which requires individuals to take the risk and the challenge of creating a new company, and to necessitate an environment to promote this individual initiative. In this sense, there are some studies that have focused on identifying the factors that encourage entrepreneurship as well as potential obstacles that limit it; among the most current and important theories is the Institutional Economic Theory, which states that there are both formal and informal factors influencing entrepreneurial activity, and where culture, which is part of the informal factors, is one of the key elements for business.

Culture combines elements that are characteristic of a society and that can be differentiated from other populations. It also determines, among other things, the behavior of individuals in society. One of the definitions of this dimension referenced from anthropology is Kluckhohn's definition (1951, p.86): “[…] culture consists of patterns of thinking, feeling and reacting, acquired and transmitted mainly by symbols, constituting the distinctive achievements of human groups, including how to make the products; the essential core of culture consists of traditional ideas and values associated”. On the other hand, from an organizational perspective, the research program GLOBE (Global Leadership and Organizational Behavior Effectiveness) defines culture as shared motives, values, beliefs, identities and interpretations or meanings of events that result from common experiences among members of a community and are transmitted from generation to generation (House et al., 2002; House and Javidan, 2004). Thus, culture plays a fundamental role in the entrepreneurial activity of a society. In this sense, some authors argue that the social and cultural context of an individual influences the corporate behavior of citizens, particularly in the creation of business, thereby constituting cultures that encourage more entrepreneurship than others (Mueller and Thomas, 2001; Reynolds et al., 2002; Li, 2007; Gurel et al., 2010).

Although there is no single definition of entrepreneurship accepted by the academic and research community (Low and MacMillan, 1988; Van Praag, 1999; Mahoney and Michael, 2004; Thurik and Wennekers, 2004), there is a general consensus that entrepreneurship is the creation of something new.

In 1730, the French economist Richard Cantillon described the entrepreneur as an individual who identifies opportunities and takes risks (Rumball, 1989). Schumpeter (1934) suggested that an entrepreneur is an individual who tends to break the balance of the market by introducing innovation within the system. Some use a broader definition such as the creation of new companies (Gartner, 1985), and many academics focus on Kirzner’s (1979) pursuit of opportunities. Harper (1996) identified that entrepreneurship is the main force of the economy and defined entrepreneurship as “[…] an activity search of profits aimed at identifying and solving specific problems in structurally complex and uncertain situations” (Harper, 1996, p.3). Over time "[...] the definition of entrepreneurship has expanded to include economic classification, management style and/or personal attitude" (Sheffield 1988, p.34).

Low (2001) defines entrepreneurship as "[...] the process of identifying, evaluating and capturing an opportunity" (Engelen et al., 2009). Moreover, George and Zahra (2002) define entrepreneurship as the acts and processes by which societies, regions, organizations or individuals identify and continue business opportunities to generate wealth. Katz and Green (2009) define the entrepreneur as "[...] a person who owns and initiates an organization" focusing on "earnings and growth" and, as indicated by Carland et al. (1984), shows a tendency to "innovative behavior".

Although there is no universally accepted definition, there is a general consensus that corporate behavior includes initiative, leadership and innovation, organization and reorganization of both economic and social mechanisms and risk taking (Lordkipanidze, 2002). Therefore, the essence of entrepreneurship is the initiation of change through creation or innovation.

As Zhao et al. (2012) suggests there are two lines of theoretical interpretation about how culture affects business. The first is rooted largely in psychological literature, and assumes that culture has a direct manifestation in the behavior of people belonging to a specific culture (Hosftede, 1980). It influences the personal values and behavior of individuals. Thus, national culture can support or prevent corporate behavior at the individual level (Hayton et al., 2002). From this perspective, a culture that supports entrepreneurship allows more people to exercise entrepreneurial potential, and in turn, increases business activity. The second line, which is based largely on institutional theory, assumes that culture, as an informal institution, is the basis of the formal institution (North, 2005). Therefore, in some countries there are institutional conditions adapted to support business activity, for example, free and competitive market, protection of private property, and an open and innovative educational system, which in turn produces more business activity in these countries. Zhao et al. (2012) describe this line as a model "culture-institution-enterprise", based heavily on Institutional Economic Theory, which includes culture as a so-called informal factor and, along with the approach of a number of investigations, one of the key factors to entrepreneurial activity. This theory suggests that the social and cultural context influences the individual, in this case, the entrepreneur, who is the agent responsible for the creation of new companies and changes in the environment.

As Veciana (1999, p.25) suggests, the Institutional Economic Theory is "[...] certainly the theory that currently provides a more consistent and appropriate conceptual framework for the study of the influence of environmental factors on the business function ". His approach is related to the influence of social and cultural factors in the context of business creation, which identify, explain and analyze the social and institutional aspects that encourage entrepreneurial activity of the individual. Díaz-Casero et al. (2005) conclude that the Institutional Economic Theory from North’s approach can be a valid theoretical framework for the study of environmental factors affecting the creation of new companies.

1.3. Culture

Culture has been defined in various ways; one of the most referenced definitions from anthropology is from Kluckhohn (1951, p.86) for whom “[…] the culture consists of patterns of thinking, feeling and reacting, acquired and transmitted mainly by symbols, constituting the distinctive achievements of human groups, including how to make the products”. For this author, the essential core of culture consists of traditional ideas and associated values. Additionally, the definition provided by the anthropologist Clifford Geertz (1973) has had great resonance among researchers, conceptualizing culture as: "[...] the sets of control mechanisms, plans, recipes, symbols, rules, constructions" (Geertz, 1973, p.44). White (1959) as an anthropologist defines culture as follows; "[...] an extrasomatic continuum (non-genetic, non-corporal) and temporal things and dependent facts of symbolization ... Culture consists of tools, implements, utensils, clothing, ornaments, customs, institutions, beliefs, rituals, games, art, language, etc." (White, 1959, p.3). Meanwhile, Hofstede (1980) defines culture as "[...] the collective programming of the mind distinguishing members of a group or category of people from others" where the "category" can refer to nations and regions within or between nations, ethnic groups, religions, occupations, organizations or genres (Hofstede, 1980; Hofstede and McCrae, 2004).

Thus, culture is used to refer to the set of values of a nation, a region or an organization; also culture shares and strengthens social institutions, and over time, these institutions, reinforce cultural values (George and Zahra, 2002). UNESCO (1982) defined culture as the set of distinctive spiritual, material, intellectual and emotional features that characterize a society or social group. While Russell et al. (2010) refer to culture as an amalgam of formal and informal institutions of a country and is associated with the practices adopted by citizens in every aspect of life. Meanwhile, Pinillos and Reyes (2011) define it as the system of values for a specific group or society, which is the development of certain personality traits, and motivates individuals toward a behavior that may not be evident in other societies. As these authors suggest, most people in a country are not aware of how culture influences their values, attitudes, ideas and norms, and most countries manifest a dominant culture.

The research program GLOBE (Global Leadership and Organizational Behavior Effectiveness) defines culture as shared motives, values, beliefs, identities and interpretations or meanings of events that result from common experiences among members of a community and are transmitted from generation to generation (House et al., 2002; House and Javidan, 2004). In addition, GLOBE sympathizes with the definition of culture proposed by Herskovitz (1948), who proposed that "[...] culture is the human part developed to fit the environment." As Mueller and Thomas (2001) show in their study based on the cultural dimensions of Hofstede (1980), culture is an underlying system of particular values to a specific group or society, which displays the development of certain features both of the personality and behavior of individuals that may not be apparent in other societies.

Table 1 contains a summary of the various definitions of culture and patterns that characterize these definitions as the statements of some authors. However, most agree that values and behavior are fundamental elements in culture.

Table 1

Definitions of culture

Author |

Definition of culture |

Key elements |

Herskovitz (1948) |

Culture is the human part developed to fit the environment |

|

Kluckhohn (1951) |

Culture consists of patterns of thinking, feeling and reacting, acquired and transmitted mainly by symbols, constituting the distinctive achievements of human groups, including how to make the products |

Traditional ideas and values |

White (1959) |

Culture is an extrasomatic continuum (non-genetic, not corporal) and temporal things and dependent facts of symbolization...Culture consists of tools, implements, utensils, clothing, ornaments, customs, institutions, beliefs, rituals, games, art, language, etc. |

Customs, beliefs, institutions, rites and language |

Hofstede (1980) |

The collective programming of the mind distinguishing members of a group or category of people from others |

Beliefs and values |

UNESCO (1982) |

The set of distinctive spiritual, material, intellectual and emotional features that characterize a society or social group |

Spiritual, material, intellectual and emotional features |

Mueller and Thomas (2001) |

Culture is an underlying system of particular values to a specific group or society, where the development of certain features both of the personality and behaviors of individuals are displayed and may not be apparent in other societies. |

Values and behaviors |

Bauman (2002) |

Culture is a separate part of the human being, a possession. Along with the personality, the unique quality of being both a defining "essence" and a descriptive "existential trait" of human creatures |

Feature |

House et al. (2002); House and Javidan (2004) |

Shared motives, values, beliefs, identities and interpretations or meanings of events that result from common experiences of members of a community and are transmitted from generation to generation |

Values and beliefs |

Russell et al. (2010) |

An amalgam of formal and informal institutions of a country and is associated with the practices adopted by citizens in every aspect of life |

Practices |

Pinillos and Reyes (2011) |

A system of values for a specific group or society, which is the development of certain personality traits and motivates individuals toward a behavior that may not be evident in other societies |

Values and behaviors |

Source: Own elaboration

1.4. Culture and Entrepreneurship

The cultural dimensions traditionally related to entrepreneurial activity and entrepreneurship include individualism, power distance and uncertainty avoidance. However, for many authors, the empirical evidence for such relationships is weak and often contradictory (Hayton et al., 2002). For example, power distance was positively related to innovation in a previous study of Shane (1992), but this relationship was negative in a later study (Shane, 1993). Thus Zhao et al. (2012) suggest that there are moderators that affect the relationship between culture and entrepreneurship. For this reason, these authors conducted an empirical study arguing that national wealth -measured as GDP per capita- is a moderating variable in this relationship, and may influence the effects of culture on entrepreneurship. Subsequently, depending on the country's wealth, the culture can have a positive or negative effect on entrepreneurial activity. This study is based on some of the cultural dimensions raised by the GLOBE project (2002, 2004), which are closely related to entrepreneurship in theory: the dimensions of a traditional society -in group collectivism, humane orientation and power distance- and the dimensions related to modernism -performance orientation, future orientation and uncertainty avoidance-, excluding the three cultural dimensions: institutional collectivism, gender egalitarianism and assertiveness. On the other hand, Ozgen (2012) presents a theoretical and conceptual article, a study about the influence of cultural dimensions proposed by the GLOBE project (2002, 2004) to support the recognition of opportunities in the emerging economies and how these cultural aspects create an impact on the recognition of opportunities by the entrepreneur and the entrepreneurial activity. His approach focused on female entrepreneurship and business activities motivated by opportunities rather than necessity.

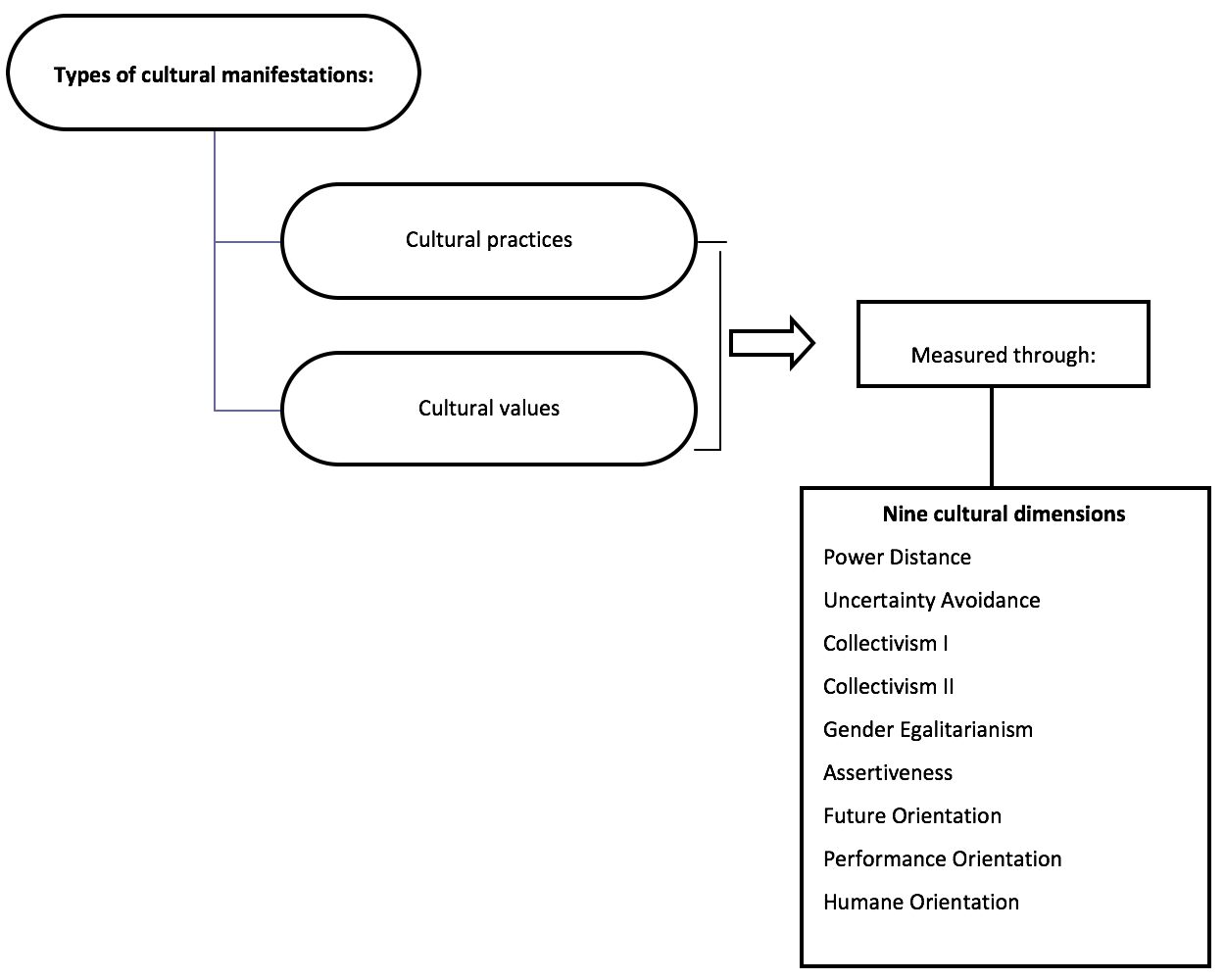

The research program Global Leadership and Organizational Behavior Effectiveness (GLOBE) House et al. (2002), House and Javidan (2004) suggest nine cultural dimensions to analyze culture: power distance, uncertainty avoidance, institutional collectivism (collectivism I), in-group collectivism (collectivism II), gender egalitarianism, assertiveness, future orientation, performance orientation, human orientation, and distinguishes between two types of cultural manifestations: cultural practices and cultural values. This approach was developed out of the psychological tradition and behavioral study of culture, and assumes that members of a particular culture should study its interpretations (Segall et al., 1998; House et al., 2010). Thus, the practices (society "is") are the perceptions of people of how things are done in their countries and values (society "should be") are the aspirations of people on the way things should be done (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Types of cultural manifestations have been studied by GLOBE

Source: Own elaboration from House et al. (2002)

From the proposal by GLOBE, previous theoretical and empirical studies linking the cultural dimensions to entrepreneurial activity are identified.

Power Distance. This dimension is defined as the degree to which members of a society expect the power to be shared unequally. Mitchell et al. (2000) suggest that a high power distance has a negative effect on business creation processes. This argument is based on the fact that in these societies, individuals of lower social class may consider entrepreneurship as a unique process for individuals of high social class, as the latter would have the necessary resources at their disposal and experience required as a result. In this way, a high proportion of population outside this small group could fail to carry out entrepreneurship in the exercise of assessment of opportunities within the context. Previous research found that entrepreneurs in cultures with low power distance will have more autonomy and negotiate with less hierarchical bureaucracy, so they are more involved in the behavior of taking risks than those in cultures with high power distance (Shane, 1993; Kreiser et al., 2010). Contrary to this argument, Ardichvili and Gasparishvili (2003) associate the high power distance with increased business activity, although not theoretically justifying this position. Meanwhile, when Hofstede (1980) refers to the dimension of power distance in the family, it is found that children in countries with high power distance are socialized to work hard and observe obedience, while in countries with low power distance the children are socialized towards independence. In this regard, the proposal is contrary to that proposed by Ardichvili and Gasparishvili (2003); however, it should be stressed that Hofstede (1980) did not relate dimensions with entrepreneurship. Therefore, it has been argued that business should be higher in countries with low power distance (Hayton et al., 2002). However, it is difficult for potential entrepreneurs underpowered groups to take advantage of profitable opportunities because they may have limited access to resources, skills, and information. Nevertheless, contrary to this position, power distance can affect the entrepreneurial activity positively because one way to demonstrate independence is to become an entrepreneur. Entrepreneurship can be used as one tool to achieve personal independence and increase one’s own position of power. The results of the study of Zhao et al. (2012) support the hypothesis that assumes there is a positive relationship between power distance and the early stages of entrepreneurship and consolidated (or established) entrepreneurship in countries with low and middle GDP, whereas there is no such relationship in countries with high GDP.

Table 2 presents a summary of the position of the authors exposed, on the level of power distance in a society and its influence on entrepreneurial activity.

Table 2.

Influence of power distance on the level of entrepreneurship

Author |

Level of Power Distance |

Influence on the level of entrepreneurship |

The author's argument |

Mitchell et al. (2000) |

High |

High |

Individuals of lower social class may consider entrepreneurship as a unique process for individuals of high social class, as the latter would have the necessary resources at their disposal and therefore experience required |

Ardchvili and Gasparishvili (2003) |

High |

High |

Associates the high power distance with increased business activity, although not theoretically justifying this position. |

Zhao et al. (2012) |

High |

High in countries with low and middle GDP |

There is a positive relationship between power distance and the entrepreneurship in countries with low and middle GDP, whereas there is no such relationship in countries with high GDP. |

Source: Own elaboration

Uncertainty avoidance. This term refers to the degree to which members seek order, consistency, structure, formalized procedures and laws that cover the situations in their daily living. Practices associated with uncertainty avoidance include aspects such as resistance to risk, and resistance to both changes and development of new products; therefore, it is estimated that a society with high uncertainty avoidance shows little support for entrepreneurship (Hayton et al., 2002). Zhao et al. (2012) proposed a hypothesis that claims uncertainty avoidance is positively associated with high entrepreneurial quality in countries with a high GDP, but the results did not support this hypothesis.

Although decisions are taken in situations where information is limited (Busenitz and Barney, 1997), individuals in cultures with low uncertainty avoidance take risks and explore some opportunities identified in their midst (Busenitz and Lau, 1996), and this finally creates a context for these types of societies in that they are more inclined towards greater entrepreneurial behavior. The same conclusion comes from Pinillos and Reyes (2011), who suggest that both the individualist and low level of uncertainty avoidance cultures are associated with the development of institutional arrangements, and possibly with psychological traits and/or cognitive processes which have been associated with entrepreneurship.

Autio et al. (2013) in their empirical study on cultural practices and their relationship to the initiative and entrepreneurial growth, based on the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor GEM and Global Leadership and Organizational Behavior Effectiveness (GLOBE), found that cultural practices of uncertainty avoidance are negatively associated with entrepreneurship but not with the aspirations of entrepreneurial growth. Similarly, Mueller and Thomas (2001) argue that cultures with low uncertainty avoidance are better-equipped and more supportive of entrepreneurs than other cultures. Table 3 shows the summary of the position of the authors regarding uncertainty avoidance and entrepreneurship.

Table 3

Influence of uncertainty avoidance on the level of entrepreneurship

Author |

Level of Uncertainty avoidance |

Influence on the level of entrepreneurship |

The author's argument |

Busenitz and Lau (1996) |

Low |

High |

Individuals in cultures with low uncertainty avoidance take risks and explore some opportunities; this finally creates a context for these types of societies who are more inclined towards greater entrepreneurial behavior |

Pinillos and Reyes (2011) |

Low |

High |

The cultures with low level of uncertainty avoidance are associated with the development of institutional arrangements and possibly with psychological traits and/or cognitive processes, which have been associated with entrepreneurship |

Mueller and Thomas (2001) |

Low |

High |

Cultures with low uncertainty avoidance are better equipped and more supportive of entrepreneurs than other cultures |

Autio et al. (2013) |

High |

Low |

Cultural practices of uncertainty avoidance are negatively associated with entrepreneurship but not with the aspirations of entrepreneurial growth |

Hayton et al. (2002) |

High |

Low |

It is estimated that a society with high uncertainty avoidance, which includes aspects such as resistance to risk and resistance to the changes, shows little support of entrepreneurship |

Source: Own elaboration

Collectivism (Institutional Collectivism). This dimension reflects the degree to which individuals are encouraged by social institutions to integrate into groups within organizations and society. In this sense, societies that value entrepreneurship and innovation introduce an efficient institutional system to promote innovative companies. Thus, the institutional environment influences the rate of economic activity, entrepreneurship and strategic actions of organizations in a society (Aldrich and Wiedenmayer, 1993; Manolova et al., 2008; Yamakawa et al., 2008). A number of authors have found that the strength of an institutional environment, such as the legal and financial system of a society shapes cognitions and the will of an entrepreneur to start a business (Mitchell et al., 2002; Lim et al., 2010). Ozgen (2012) proposed theoretically that individuals in societies of high institutional collectivism perceive the results of its business efforts as desirable, because these companies strengthen the socio-cultural infrastructure of society, establish systems of support to the training and facilitate business activities and the creation of new companies (Steier, 2009).

On the other hand, according to empirical studies, potential entrepreneurs in societies in low institutional collectivism may face socio-cultural barriers, such as negative public attitude towards creativity and innovation, legal institutional barriers and regulatory complexities, strict administrative processes, bureaucratic procedures (Grilo and Thurik, 2005; Klapper et al., 2006), and the difficulty in accessing credit or lack of specific training programs (Ozgen, 2012), among others.

Collectivism II (In group-Collectivism). This dimension refers to the pride and loyalty to family, and to the close circle of friends and organizations of which the individual is a member. Tiessen (1997) mentions that researchers have associated individualist cultures with the business behavior of the individual as founder or individual entrepreneur, while collectivist societies seem more inclined to promote corporate entrepreneurship. Moreover, in such societies that dominate the collective economic activity, there are few opportunities for individuals to develop the skills and abilities necessary to create new companies (Mitchell et al., 2000). By contrast, Pinillos and Reyes (2011) mentioned in their research that some studies based on empirical support, as studies Hunt and Levie (2003) and Baum et al. (1993) have shown a positive relationship between collectivism and entrepreneurial activity. Specifically, the rate of entrepreneurship in a country is negatively related to the dimension "individualism" when the country's development is medium or low, and is positively related when the level of development is high; therefore, individualism is not related to entrepreneurship in the same way in countries with different levels of development.

The collectivist orientation fosters commitment and sacrifice among employees (Gelfand et al., 2004) and provides a protective environment that minimizes the uncertainty associated with business creation and application of innovation (Stewart, 1989). However, as indicated by Zhao et al. (2012), these aspects are only important in countries with low and middle GDP rather than countries with high GDP due to the availability of alternative resources in the latter. It is only in countries of the low and middle GDP that startup entrepreneurs need to be able to use these traditional resources of in-group collectivism.

It is clearly seen in Table 4, which summarizes the position of some authors on the relationship between the level of in-group collectivism of a society and its level of entrepreneurship, Mitchell et al. (2000) and Hayton et al. (2002) coincide in their views, indicating that in a society with a high level of in-group collectivism a higher level of entrepreneurship is perceived.

Table 4

Influence of collectivism II on the level of entrepreneurship

Author |

Level of Collectivism II |

Influence on the level of entrepreneurship |

The author's argument |

Mitchell (2000) |

High |

Low |

In collectivist societies, which dominate the collective economic activity, there are few opportunities for individuals to develop the skills and abilities necessary to create new companies |

Hayton et al. (2002) |

High |

Low |

In-group Collectivism is negatively related to entrepreneurship, because it is an activity of enterprising individuals who are rewarded individually |

Oyserman et al. (2002) |

Low |

High |

Individualism has been a key dimension to understanding entrepreneurial behavior |

Pinillos and Reyes (2011) |

High |

High in countries with low or middle GDP |

In societies with low or middle GDP and a high level of in-group collectivism, increased business activity is estimated |

Zhao et al. (2012) |

High |

High in countries with low or middle GDP |

In societies with low or middle GDP and high level of in-group collectivism, increased business activity is estimated |

Source: Own elaboration

Assertiveness. This dimension refers to the extent to which individuals are (or should be) assertive, confrontational and aggressive in social relationships. In highly assertive societies people may be encouraged to take risks, negotiate aggressively and be competitive, while in the less assertive societies, harmony and supportive relationships (Ozgen, 2012) are encouraged. Little or nothing has been published on the relationship of this dimension to entrepreneurship; however, from a theoretical perspective, Ozgen (2012) suggests that a lower level of assertiveness in society will produce less entrepreneurship by opportunity.

Humane orientation. This is the degree to which individuals in organizations or societies encourage and reward others to be fair, altruistic, friendly, generous and caring with others, and according to empirical studies as developed by Zhao et al. (2012), a society of low or middle GDP and high level of humane orientation is driven towards entrepreneurship.

Entrepreneurship is a systemic phenomenon that requires individuals who are willing to take the risk and the challenge of creating and developing a venture. In this sense, there are some studies that have focused on identifying the factors that promote or inhibit entrepreneurship; among the most influential currents is the Institutional Economic Theory, which suggests that there are formal and informal factors influencing entrepreneurial activity, being the culture of the so-called informal factors and one of the key aspects for the development of entrepreneurial activity.

Among the models found in the literature to identify the cultural dimensions of society in studies of organizational field, the one conducted by GLOBE stands out (House et al., 2002; House and Javidan, 2004), in which the relationship between culture and leadership is studied, but the relationship of culture with entrepreneurial activity were not analyzed. GLOBE raises nine cultural dimensions to identify cultural practices (society "is") and cultural values (society "should be") of a society. From these cultural factors authors have developed studies that conclude that the dimensions that are related to business activity are: Power Distance (Mitchell et al., 2000; Ardichvili and Gasparishvili, 2003; Zhao et al., 2012), Uncertainty Avoidance (Busenitz and Lau, 1996; Pinillos and Reyes, 2011; Mueller and Thomas, 2001; Autio et al., 2013; Hayton et al., 2002), Collectivism I (Mitchell et al., 2002; Lim et al., 2010; Ozgen, 2012; Grilo and Thurik, 2005; Klapper et al., 2006), Collectivism (Mitchell et al., 2000; Hayton et al., 2002; Pinillos and Reyes, 2011; Zhao et al., 2012), Assertiveness (Ozgen, 2012) and Humane Orientation (Zhao et al., 2012).

Thus Ardichivili and Gasparishvili (2003) and Zhao et al. (2012) agree in their positions, claiming that the high level of power distance in a society significantly influences entrepreneurial activity. By contrast, Mitchell et al. (2000) indicates that in societies with high power distance, the entrepreneurial activity will be lower, since it can be considered that individuals from higher socio-economic strata have the resources required to start entrepreneurial activity, unlike those in low economic positions. On the other hand, the authors that have performed studies on the dimension of uncertainty avoidance and its relationship with the entrepreneurship coincide with the position that in societies with a higher level of uncertainty avoidance, less entrepreneurial activity has been observed

The approaches of the authors consulted on the institutional collectivism dimension agree that in cultures with a low level of institutional collectivism, a low level of entrepreneurship is reflected. While, on the relationship between the level of in-group collectivism of a society and its level of entrepreneurship, Mitchell et al. (2000) and Hayton et al. (2002) coincide in that in a society with a high level of in-group collectivism, a higher level of entrepreneurship is perceived. Similarly, but with reference to individualism, Oyserman et al. (2002) argue that individualism is a major cultural feature for entrepreneurship. While in the case of Pinillos and Reyes (2011) and Zhao et al. (2012) the studies include Gross Domestic Product GDP as a moderating variable, and therefore conclude that in societies with a low or middle GDP and with a high level of in-group collectivism, greater entrepreneurial activity is estimated. Regarding the cultural dimension, assertiveness there is a deficient number of publications on the relationship of this dimension with entrepreneurship; in this case, only the theoretical study by Ozgen (2012) was found, claiming that the lower the level of assertiveness in society, the less opportunities for entrepreneurship will be evident. Finally, on the cultural dimension of humane orientation, according to the literature review, there are few studies addressing its relationship with entrepreneurship; in this case, the only empirical study found was by Zhao et al. (2012) which concluded that a society of low or middle GDP and with a high level of humane orientation can lean towards more entrepreneurial activity. There have only been a few empirical studies addressing the relationship of culture and entrepreneurship from the proposed cultural dimensions by the GLOBE project. This may be due, in principle, to the purpose of the GLOBE project which was to analyze the relationship of culture with leadership and not with entrepreneurship and, secondly, could be considered as a relatively new proposal, to characterize the culture of a society. Thus, of the nine cultural dimensions of GLOBE, six dimensions are related to entrepreneurial activity, according to previous studies. Specifically the relationship of entrepreneurship with dimensions: Power Distance, Uncertainty Avoidance, Institutional Collectivism, In-group Collectivism, Gender Egalitarianism, Future Orientation, Performance Orientation and Humane Orientation, has been supported empirically, whereas in the case of the cultural variable of Assertiveness, only one theoretical proposal has been made concerning its influence on entrepreneurship.

Aldrich, H.E. & Wiedenmayer, G. (1993). From traits to rates: an ecological perspective on organizational and Inclusive Development. Advances in entrepreneurship, firm emergence, and growth, 145-195.

Ardichvili, A. & Gasparishvili, A. (2003). Russian and Georgian entrepreneurs and non-entrepreneurs: a study of value differences. Organization Studies, 24(1), 29–46.

Autio, E., Pathak, S. & Wennberg, K. (2013). Consequences of cultural practices for entrepreneurial behaviors. Journal of International Business Studies, 44(4), 334-362.

Baum, J. R., Olian, J. D., Erez, M., Schnell, E. R., Smith, K. G., Sims, H. P., et al. (1993). Nationality and work role interactions: A cultural contrast of Israeli and US entrepreneurs' versus managers' needs. Journal of Business Venturing, 8(6), 499-512.

Busenitz, L. W. & Barney, J. B. (1997). Differences between entrepreneurs and managers in large organizations: biases and heuristics in strategic decision-making. Journal of Business Venturing, 12(1), 9–30.

Busenitz, L. W. & Lau, C. M. (1996). A cross-cultural cognitive model of new venture creation, Entrepreneurship. Theory and Practice, 20, 25–39.

Carland, J.W., Hoy, F., Boulton, W. & Carland, J.A.C. (1984). Differentiating entrepreneurs from small business owners: a conceptualization. Academy of Management Review, 9(2), 354-359.

Díaz-Casero, J. C., Urbano-Pulido, D. & Hernández-Mogollón, R. (2005). Teoría económica institucional y creación de empresas. Investigaciones Europeas de Dirección y Economía de la Empresa, 11(3), 209-230.

Engelen, A., Heinemann, F. & Brettel M. (2009). Cross-cultural entrepreneurship research: Current status and framework for future studies. Journal of International Entrepreneurship, 7(3), 163-189.

Gartner, W. B. (1985). A conceptual framework for describing the phenomenon of new venture creation. Academy of management review, 10(4), 696-706.

Geertz, C. (1973). The interpretation of cultures: Selected essays (Vol. 5019). Basic books.

Gelfand, M. J., Bhawuk, D. P. S., Hishi, L. H., & Bechtold, D. J. (2004). Individualism and collectivism. En House, R.J., Hanges, P.J., Javidan, M. & Dorfman, P.W. & Gupta, V. (Eds.), Culture, leadership, and organizations: The GLOBE study of 62 societies (437-512). Thousand Oaks, CA.: Sage.

George, G. & Zahra, S.A. (2002). Culture and its consequences for entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 26(4), 5-8.

Grilo, I. & Thurik, R. (2005). Latent and actual entrepreneurship in Europe and the US: Some recent developments. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 1(4), 441-459.

Gurel, E., Altinay, L. & Daniele, R. (2010). Tourism student’s entrepreneurial intentions. Annals of Tourism Research, 37(3), 646–669.

Harper, D. A. (1996). Entrepreneurship and the Market Process, London: Routledge.

Hayton, J. C., George, G. & Zahra, S. A. (2002). National culture and entrepreneurship: A review of behavioral research. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 26(4), 33-52.

Herskovitz, M.J. (1948). Man and His Work: The Discipline of Cultural Anthropology, New York: Knopf.

Hofstede, G. & McCrae, R. (2004). Personality and culture revisited: Linking traits and dimensions of culture. Cross-Cultural Research, 38(1), 52-88.

Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture’s consequences: International differences in work-related values, Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

House R.J., Quigley N.R. & De Luque M.S. (2010). Insights from Project GLOBE Extending global advertising research through a contemporary framework. International Journal of Advertising, 29(1), 111-139.

House, R., Javidan, M., Hanges, P. & Dorfman, P. (2002). Understanding cultures and implicit leadership theories across the globe: An introduction to project GLOBE. Journal of World Business, 37(1), 3–10.

House, R.J. & Javidan, M. (2004): Overview of GLOBE. En House, R.J., Hanges, R.J., Javidan, M., Dorfman, P.W. & Gupta, V. (Eds), Culture, Leadership, and Organizations: The GLOBE Study of 62 Societies (9-26).Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Hunt, S., & Levie, J. (2003). Culture as a predictor of entrepreneurial activity. En W. D. Bygrave (Ed.), Frontiers of entrepreneurship research 2003 (171–185). Wellesley, MA: Babson College.

Katz, J. A. & Green, R. P. (2009). Entrepreneurial small businesses. (2nd ed.). Irwin NY: McGraw-Hill.

Kirzner, I. M. (1979). Perception, Opportunity and Profit: Studies in the Theory of Entrepreneurship. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Klapper, L., Leaven, L. & Rajan, R. (2006). Entry regulation as a barrier to entrepreneurship. Journal of Financial Economics, 82(3), 591-629.

Kluckhohn, C. (1951). The study of culture. En Lerner, D. & Lasswell, H.D. (Eds.), The policy sciences. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Kreiser, P.M., Marino, L.D., Dickson, P. & Weaver, K. M. (2010). Cultural influences on Entrepreneurial orientation: The impact of national culture on risk taking and proactiveness in SMEs. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 34(5), 959-983.

Li, L. (2007). A review of entrepreneurship research published in the hospitality and tourism management journals. Tourism Management, 29(5), 1013-1022.

Lim, D.S.K., Morse, E.A., Mitchell, R.K. & Seawright, K.K. (2010). Institutional environment and entrepreneurial cognitions: A comparative business systems perspective. Entrepreneurship theory and Practice, 34(3), 491- 516.

Lordkipanidze, M. (2002). Enhancing Entrepreneurship in Rural Tourism for Sustainable Regional Development: The case of Söderslätt region. Sweden, Published by IIIEE, Lund University, PO Box, 196.

Low, M. B., & MacMillan, I. C. (1988). Entrepreneurship: Past research and future challenges. Journal of management, 14(2), 139-161.

Low, M.B. (2001). The adolescence of entrepreneurship research: specification of purpose. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 25(4), 17-25.

Mahoney, J. & Michael. S. (2004). A subjective theory of entrepreneurship. En Alvarez, S. (Ed.), Handbook of Entrepreneurship. Boston, MA: Kluwer, forthcoming

Manolova,T. S., Eunni, R. & Gyoshev, B. S. (2008). Institutional environments for entrepreneurship: evidence from emerging economies in Eastern Europe. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 32(1), 203-218.

Mitchell, R. K., Smith, B., Sewright, K. W. & Morse, E. A. (2000). Cross-cultural cognitions and the venture creation decision. Academy of Management Journal, 43(5), 974–993.

Mitchell, R. K., Smith, J. B., Morse, E. A., Seawright, K. W., Peredo, A. M., & McKenzie, B. (2002). Are entrepreneurial cognitions universal? Assessing entrepreneurial cognitions across cultures. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 26(4), 9-33.

Morrison, A. J., Rimmington, M. & Williams, C. (1999). Entrepreneurship in the Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure Industries. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann.

Mueller, S. & Thomas, A. (2001). Culture and Entrepreneurial Potential: A Nine Country Study of Locus of Control and Innovativeness. Journal of Business Venturing, 16(1), 51-75.

North, D. C. (2005). Understanding the process of economic change. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Oyserman, D., Coon, H. M. y Kemmelmeier, M. (2002). Rethinking individualism and collectivism: Evaluation of theoretical assumptions and meta-analyses. Psychological Bulletin, 128(1), 3–72.

Ozgen, E. (2012). The effect of the national culture on female entrepreneurial activities in emerging countries: an application of the GLOBE Project cultural dimensions. International Journal of Entrepreneurship, 16, Special Issue, 69-92.

Pinillos M.J. & Reyes L. (2011). Relationship between individualist–collectivist culture and entrepreneurial activity: evidence from Global Entrepreneurship Monitor data. Small Business Economics, 37(1), 23-37.

Reynolds, P. D., Bygrave, W. D, Autio, E., Cox, L. W. and Hay, M. (2002). Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (Kansas City: Kauffman Foundation).

Rumball, D. (1989). The Entrepreneurial Edge: Canada’s Top Entrepreneurs Reveal the Secrets of their Success. Toronto: Key Porter.

Russell, S. S., Nabamita, D. & Sanjukta, R. (2010). Does cultural diversity increase the rate of entrepreneurship?. The Review of Austrian Economics, 23(3), 269-286.

Schumpeter, J. A. (1934). The theory of economic development: An inquiry into profits, capital, credit, interest, and the business cycle. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Segall, M.H., Lonner, W.J. & Berry, J.W. (1998). Cross-cultural psychology as a scholarly discipline: on the flowering of culture in behavioral research. American Psychologist, 53(10), 1101-1110.

Shane, S. (1992). Why do some societies invent more than others?. Journal of Business Venturing, 7(1), 29-46.

Shane, S. (1993). Cultural influences on national rates of innovation. Journal of Business Venturing, 8(1), 59-73.

Sheffield, E. A. (1988). Entrepreneurship and Innovation: In Recreation and Leisure Services. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance, 59(8), 33-34.

Steier, L.P. (2009). Familiar capitalism in global institutional contexts: Implications for corporate governance and entrepreneurship in East Asia. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 26(3), 513-535.

Stewart, A. (1989). Team entrepreneurship. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

Thurik, A.R. & Wennekers M. (2004). Entrepreneurship, small business and economic growth. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 11(1), 140–149.

Tiessen, J. H. (1997). Individualism, collectivism and entrepreneurship: a framework for international comparative research. Journal of Business Venturing, 12(5), 367–384.

UNESCO. "Conferencia Mundial sobre las Políticas Culturales" (1982). Disponible en: http://www.unesco.org/new/es/mexico/work-areas/culture/

Van Praag, C. M. (1999). Some Classic Views on Entrepreneurship. De Economist, 147(3), 311–335.

Veciana, J.M. (1999). Creación de Empresas como programa de investigación Científica. Revista Europea de Dirección y Economía de la Empresa, 8(3), 11-36.

White, L. A. (1959). The Concept of Culture. American anthropologist, 61(2), 227-251.

Yamakawa, Y., Peng, M.W. & Deeds, D. L. (2008). What drives new ventures to internationalize from emerging to developed economies?. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 32(1), 59-82.

Zhao, X., Li, H., & Rauch, A. (2012). Cross-Country Differences in Entrepreneurial Activity: The Role of Cultural Practice and National Wealth. Frontiers of Business Research in China, 6(4), 447-474.

1. PhD in scientific perspectives on tourism and management of tourism companies. Researcher Professor, University of San Buenaventura Cali, Cali, Colombia. E-mail: mcastillop@usbcali.edu.co

2. PhD in economic and business sciences. Vice-Rector for Entrepreneurship and Employment, University of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Spain. E-mail: rosa.batistacanino@ulpgc.es

3. PhD in scientific perspectives on tourism and management of tourism companies. Full Professor, Departamento de Ciencias Turísticas.Facultad de Ciencias Contables, Económicas y Administrativas. Universidad del Cauca, Colombia. E-mail: alexanderzuniga@unicauca.edu.co